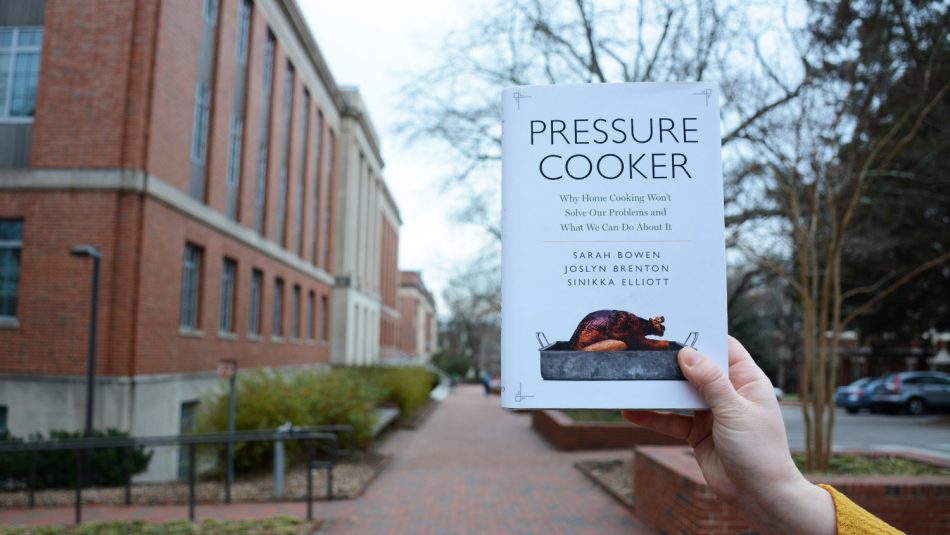

Wolfpack Writers: Sarah Bowen

Sarah Bowen is an associate professor of sociology at NC State. Her book Pressure Cooker: Why Home Cooking Won’t Solve Our Problems and What We Can Do About It, which is coauthored by Joslyn Brenton and Sinikka Elliott, tells the complicated story of what it takes to feed a family in America today. We caught up with Bowen to learn more about her in-depth research, travel and busy life as a writer.

Why this story? What motivated you to tell it?

In the face of lots of (understandable) concerns about the food system — things like food safety scares, confusion about which foods are the healthiest, and worries about the environmental impact of our food choices — lots of people are looking to the kitchen for answers. Specifically, there is this idea that by cooking more at home, families can become healthier and happier. But few people have actually asked people what it’s actually like to feed a family. Organized around the stories of nine families in and around Raleigh, our book takes on seven foodie myths, showing how encouraging people to “cook from scratch” and “get back into the kitchen” is not going to solve the problems in our food system. Instead, we need to focus on the broader inequalities that shape how people eat and feed their families.

What kind of research did you do for Pressure Cooker?

The book comes out of a five-year study that I conducted with my coauthors, Joslyn Brenton and Sinikka Elliott, and a team of researchers at NC State. In 2012 and early 2013, we interviewed more than 150 mothers and a handful of grandmothers who were primary caregivers of young children. We asked women to tell us what they ate, who cooked and shopped for food in their households and what they believed about food and health. Most of the participants (138) were from poor or working class families. Another 30 were from middle and upper middle-class families. The following year, we invited 12 lower-income families to participate in extended ethnographic observations. We spent a total of more than 250 hours with them: going grocery shopping with them, tagging along on visits to doctors and social services offices, and hanging out in their homes as they made and ate meals.

You juggle a lot. How does a professor make time to write?

It’s hard! I tell my students that the best way to write is to do a little every day, instead of waiting for a big block of time, and that’s what works best for me. I try to prioritize writing for at least an hour a day. It doesn’t always work out, but I can make a lot of progress if I’m writing regularly, even for just an hour at a time.

In one word, what do you need to overcome writer’s block?

Feedback (often from my coauthors).

When do you read?

I read for work (for my research or the courses I’m teaching) during the day and sometimes in the early evening. I also read a lot of fiction, and I mostly read those books right before bed. I’ve been traveling a lot this semester, and one benefit is that I’ve read a lot of good books on the plane!

When do you write?

My favorite time to write is in the morning, before the chaos of the day really starts, but I write whenever I find time to sneak it in.

What book should everybody read before the age of 21?

I’m going to decline to answer this question. There are so many books that have meant so much to me that it feels impossible to pick just one. My favorites are the books that transport me to another time or place (or both!) and let me see the world from another perspective. And as a person who studies food, I am always paying attention to how food is used in literature. Recently, I loved all the food scenes in Pachinko by Min Jin Lee, where food is a symbol of people’s journeys across borders, their search for home in new places and mothers’ care for their families. Ruth Ozeki’s My Year of Meats was one of the first examples of “food fiction” I ever read. I loved how she used food to tell a story about gender, families and the industrial food system, and that book has stuck with me ever since.

What’s next for you? Another book, something else?

I’m sure I have another book up my sleeve! I recently spent a year on research leave in Sweden with my family, and I’d like to write a book that compares what it’s like to raise children and live in the United States and Sweden through the lens of food.

- Categories: