Meet the Faculty: Dr. Sasha Newell

We pride ourselves on the research coming out of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology. Our faculty have contributed to the breadth and depth of the discourse in their research areas. Ranging from political economy to craniofacial growth, those research areas are as diverse as the complex human endeavor our faculty strive to analyze and understand. Ultimately, their fine research aids us in understanding human behavior and relationships, the foundations of human cultures and societies, which each of our faculty explores from a distinct perspective.

Today, we meet Dr. Sasha Newell, who joined the Department of Sociology and Anthropology in the 2012-2013 academic year as an Assistant Professor specializing in Sociocultural Anthropology.

Navigation

Could you begin by giving us a little information on where you’re from?

I grew up in northeast Vermont, the Northeast Kingdom, which is the far corner of Vermont near Canada and New Hampshire. My parents moved up there in the 70s. They were back-to-the-landers, and bought a pretty sizeable piece of land for a tiny bit of money. It’s a really bad place to try to live off the land, though, because there are only three months of the year with no frost. I don’t think they were really ever able to survive from their own garden, although my dad still keeps up a vegetable garden. They survived off of odd jobs for a while and ended up being elementary school teachers and eventually helped found an elementary school. The most interesting part of my upbringing is that we lived off the grid. They started off with just wood heat and propane lights, and then we got solar panels during the Carter administration when there was a subsidy for that. We heated water on the stove until I was 9. In the winter we had to walk a 3rd of a mile through the snow to get to the plowed road. They hooked up to the grid just a few years ago because we started worrying about them having a backup heat system if they got sick.

You lived in northeastern Vermont until you left for college?

I went to a Waldorf boarding school in New Hampshire for high school, actually. It’s too long a story how I ended up there, but I was fleeing a local school system I had quickly lost respect for. But I was still in weekend driving distance from my parents. When I really left home for college, I went to Oregon.

What college did you attend in Oregon and what did you study?

I went to Reed College and studied anthropology. But before I went to college, I spent a year abroad. I got the idea, somehow, that I shouldn’t go to college right away, that I should take some time to learn about “the real world.” My parents were supportive, but said “Ok, but we don’t want you just wasting years, so you have to do something interesting.” And they have always valued travel – they actually met in Paris. I found these exchange programs that I could do in Kenya and Nepal and went to do year abroad. I didn’t know what anthropology was at the time, but I was on the path already, as far as experiences go. When I got to college, I still didn’t know what anthropology was. I was already interested in behavior, so I thought I might major in psychology. As soon as I read about anthropology in the course catalogue, I knew I wanted to try it. But they didn’t allow you to take anthropology until you were a sophomore at Reed College. They didn’t think you were intellectually mature enough. (Laughter) I took it as soon as I could sophomore year. That was 1993. I’ve been an anthropologist ever since.

I was drawn to anthropology because I’d had those experiences of pretty intense travel. I lived in a mud hut in Kenya with a family and ate just what they ate. In the exchange programs we went through a preparatory group cultural training session, and a big part of those conversations was about understanding colonial history, and the effects it had on Kenyan people and their perspective on race and Western culture. I was in a village where they hadn’t seen anyone white since the missionaries came through. It was hard to walk around without a horde of kids following me, making camera motions, and yelling “Mzungu.” I couldn’t even bathe properly because the only place to bathe was behind the hut with a bucket, and people would see me from the other hillside and start pointing and yelling. Because whiteness was associated with Christianity, this old man stopped me on the side of the road and wanted me to bless his home. I didn’t really know what to do and decided that it was easier to go along with it than to explain that I didn’t think I had the capacity to bless. Then he wanted me to bless another one. And a white woman who was in a neighboring village had someone think that it was judgment day and she was an angel. So, I had all these experiences that required explanation, they required a lot of thinking and I did not have many tools to do it with. So, like I said, I thought psychology because that was the only discipline I knew that was about behavior and then when I realized that there was something specifically about understanding cultural differences, I was immediately drawn to it. I was drawn to it primarily intellectually. Those questions kept pulling me in.

Did you take more time off after your undergraduate studies or did you go straight into graduate study?

I went to Cornell University directly from Reed College. I was friends with people a year ahead of me, mostly, and I watched them struggle after graduating. It was very hard to get a job in Portland in those days. It still is. And I thought, Well, I’m really liking school. I might as well keep doing it. I’d already had that year of non-academic experience, and I thought that was enough. Now I wish I had more non-academic work experience.

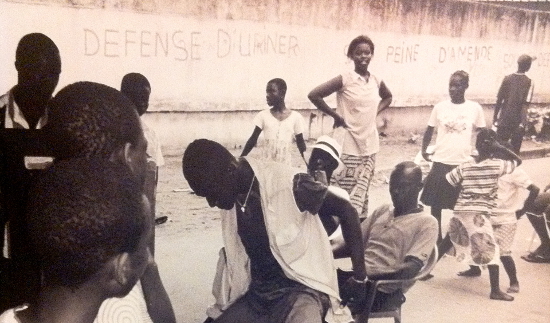

But Reed had already shaped me as an academic, because, you had to perform fairly intensive academic research. All the people who graduate from Reed have to write a thesis and defend it in front of a panel of faculty, very much like graduate school. Mine was on some of the stuff that I continue to work on – on Congolese sapeurs, who are young men who dress in suits. It’s a subculture through which they get a lot of prestige. They are known as Parisians because they go to Paris to buy their suits. It’s almost like a religion of clothing. There’s this really powerful relationship between the clothes and the transformative potential of clothing. For a while, in the 80s, they were shaving their heads to look bald and wearing padding around their stomach and buttocks to look more like businessmen. So, I was trying to explore that by looking far back into the history of the encounter between the Congo and the Portuguese, and the ways in which European things got tied in with the structure of the Kingdom of Kongo back in the 1500s, and tracing that into contemporary structures of taste and consumption. Not to suggest that culture and society haven’t changed drastically since those days, but that there is a long history of appropriating foreign goods as prestige items that informs contemporary consumption patterns. So I was still very interested in those themes when I got to graduate school. I actually planned on going to Congo-Brazzaville for my research but it became too dangerous because of the civil war underway in the late 1990s. So, I thought of either going to Paris to work on the Congolese migrants there or to the Cote d’Ivoire where I’d read about people imitating the Congolese sapeurs. I thought an imitation of an imitation was interesting. I ended up doing both projects. That work became the foundation of my dissertation at Cornell.

I finished my degree there in 2003, and I became a kind of itinerant professor, teaching at a variety of places, including NYU, University of Illinois, University of Virginia, and College of the Holy Cross, before coming here to join my wife Diana Arbaiza, who teaches Spanish literature and culture in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures.

What courses do you currently teach?

I currently teach Anthropology 252, or Cultural Anthropology, every semester. I also teach a regional course on Africa which is currently called Peoples and Cultures of Africa. Elsewhere I have taught this as Urban African and Popular Culture, and I plan to change the course once I get the paperwork approved. Africa has the most rapidly growing cities in the world, and many people argue that these megacities resemble what cities in the future will be like. These cities have a very dynamic and changing culture because of the rapid growth and intense mixture of languages, religions, and ethnicities, and I think it is important for students to realize how important these urban spaces are to Africa today. I also teach Anthropology of Religion and Anthropological Theory.

Could you describe your teaching style or philosophy?

I’m not a fan of the idea of the teacher pouring the cup of knowledge into the student-as-recipient. I think that knowledge is something that we construct collectively, whether we realize it or not. I try to make the class a place in which we’re conscious of that construction process. As much as possible, I try to get students to engage with each other and with me in the classroom. I try to destabilize as many aspects as possible of what they think the world is, which they don’t always take well to. I think often they get more out of it than they realize at first. You can see evidence of that when you see the students coming back for another course. Of course, people who are more inclined to cling to “facts” are less likely to come back. I try to create a critical approach to knowledge but I also want them to feel responsible for their own knowledge. I try to get them to read more critically. I don’t use textbooks. I use texts that anthropologists write for each other. I tell them that the reading is going to be more challenging and that the class is going to be about trying to understand together what the reading is about, it’s significance for our conversation, and in that way to not just accept what the reading says is true and also to not just accept as true anything that we come across. I care less about the content of what they learn than about their ability to think from an anthropological perspective.

What do you think are the most important attributes of a good instructor?

Perhaps to a fault, I believe in the accessibility of the instructor. I try to downplay hierarchy and create this kind of collective knowledge-building atmosphere. Sometimes, I think about my best teacher in college who was one of the most frightening women I’ve ever encountered. (Laughter) People left her classroom crying on a regular basis. But we did the readings for her class. So, there is an effectiveness to fear, I suppose, but that just isn’t me. I strive to make the classroom a dynamic place in which students challenge themselves and each other to think in new ways, where on any given day the world as you know it could tilt under your feet as you see it from another perspective entirely.

How do you define success and what does a student need to do in order to be successful in your class?

When they come to class not only having done the reading but wanting to understand and know more about it. When they come with questions. When they, themselves, connect the dots between different readings. When they start using the anthropological perspective to think critically about their own world. Of course, if we are talking about grades, these phenomena have to manifest in the writing as well in the form of coherent arguments that pull together the readings and ideas from the course… but they nearly always do, if the student is truly interested.

If you could create and plan your dream course, what course would it be?

I have a lot of those, but I guess I’ll talk about Anthropology of the Undead, which is a course I’ve thought of recently, and which would investigate the different ways that people around the world construct the space after death. It would explore the symbolic origins of stories about zombies and vampires but also look cross-culturally at how similar beliefs about spirit creatures and monsters of various sorts exist across the world and throughout history. Essentially, the course explores the imagination of the space of death and how that affects many of our actions and perspectives in the world of the living. A lot of this involves witchcraft and witches as these evil agents that inhabit our society but actually, beneath the surface, they’re trying to kill us or eat us. In West Africa, your own family members are always the ones who are the witches. They are the only ones who can actually do any harm to you. And they’re trying to eat you. If they eat you in the other world, then you’ll die in this world. They look just like humans, they fit into society, but under the surface they’re secretly plotting to destroy us. What’s amazing about this idea is that it’s almost everywhere, often in secular spaces as well, such as the McCarthyist figure of the communist. The more contemporary figure of the terrorist in contemporary US society fits this quite well. Bush talked about them as evil beings living in dark caves, but he also described them as living invisibly amongst us, plotting the destruction of freedom and our way of life. So, that’s one course. But my favorite thing to teach about is probably consumption and exchange – the way in which material objects become incorporated into social life and cultural meaning.

Does teaching inform or influence your research in any way?

They are always in a dialectic, for me. I find that I do a lot of my best research through teaching. I like to make up new courses and I learn a lot from that process of knowledge-building. One of the things about teaching is that you have to make things that you take for granted explicit. Ideas that have become kind of crusty and are no longer really ideas so much as structures limiting your thought, once you have to explain them to people they return to being ideas that you can think critically about and, perhaps, cast off. I actually find that when I have time off, I’m not able to think as well because I don’t have to explain myself.

Can you tell us about your current research interests?

I’ve been an Africanist my whole career but in recent years I’ve had this side project that’s now become more central, which is looking into US storage space (not just storage units, but attics, basements, closets, even shoeboxes). I’m exploring storage space from various levels, thinking about what the architectural space is and how that works symbolically in our culture, the relationship between the public space of the home and then this kind of hidden space. The whole issue of hoarding is important. It’s now considered a psychological disorder and has recently been listed in the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders).

But my perspective is to examine in what ways hoarding is a hyperbolic version of something that is quite normal in our society. While interviewing all these people and going through their stuff with them, it becomes apparent that their same tendencies exist through a huge amount of society. In fact, even the logic for why minimalists or purgers can’t stand to have things around them is the same as those who can’t get rid of it. They don’t want the weight of the personhood vested in those objects. Like, this woman who shed everything from her former relationships, most of her stuff, because she didn’t want anything that represented those people from the past in any way. She didn’t want anything from her mother in her house. She didn’t want anything from her former husband. She didn’t want anything from her current boyfriend, really, because she didn’t want to be tied down by those relationships. I became interested in this because of this issue of things with animacy, something our culture denies that we believe in. My argument for the things that people keep in storage is that most of the reason we can’t get rid of these items is because we feel that have too much personhood inside them. We deny that because we’re not supposed to believe that objects can have personhood inside them. So, we can’t even articulate why they’re important to us. My project demonstrates that in fact most people treat some objects as being more than material, as having personhood or social agency (and for this very reason, many of them are hidden away).

My initial entry into this has been to think about it as an Africanist. The way in which people relate to material things, particularly the way in which West Africans relate to material objects differently from us, tells a lot about our own behavior. And maybe the difference is more apparent than real. This goes back to the whole history of Europeans in Africa and all of the misunderstandings that have happened. The Europeans thought that Africans were fetishists, meaning that they (Africans) worshipped objects that they made themselves and that they thought were gods, somehow. The idea of the fetish became an important source of social theory and critique, especially through Marx and Freud. But this is all based on the idea that Africans misunderstood their own world. These thinkers accused their own society of being “primitives.” What I’m interested in doing in this article that I’ve been working on is to take seriously the West Africans actually interact with objects that they think have personhood inside them and use that as a model for thinking critically about our own society.

What theoretical framework are you working out of?

Part of it comes from classic Mauss, the idea of the person in the thing, the person in the gift. But here I’m looking not at gifts but at commodities. It’s the idea that the things that we buy start to absorb personhood to the point at which it’s no longer possible to sell them or throw them away. Even if they have great value, people often feel they can’t part with it because it’s too inmeshed in their family. The responsibility of the family is what keeps them from selling it, even if they don’t care about the gift. They owe it to their family to pass it on to other members of the family. All of that is about the sociality of objects, but objects aren’t just signs of sociality but actually take on a role with some agency and they affect our behavior, obligating us to behave in certain ways. I’m rethinking the study of consumption, which has largely been about display, and I’m trying to emphasize what happens behind the scenes and the ways in which objects get incorporated into daily life and become part of us and, even, part of kinship, that objects are members of families, too.

Another layer to that is that I’m also interested in consumption as a form of magical efficacy, that a lot of the ways that people relate to objects are semiotic processes where we try to draw value from objects. Either through indexicality, which is about the history of contact of that object – and gift economies are all about the value of the gift as the history of people who have had it before – or through iconicity, or metaphor, where it’s about the image of the object. Consumption in the US is understood mostly as being about image, but there are lots of things that we value because of their history of contiguity, their history of contact, including antiques and things that belonged to celebrities. I think focusing on that aspect, on the way in which people get value out of those semiotically, allows you to look cross-culturally and get past the gift vs. commodity dichotomy that anthropology has a hard time getting past when thinking about globalization.

How did this research project begin?

That’s a novel… I’ve moved at least twelve times in the past ten years, and that gives you a very intimate understanding of what you own. (Laughter) And how it literally and emotionally weighs on you. I also come from a family for which clutter is very normal and even comes close to hoarding in some cases. So, I’ve dealt with some of these issues my whole life and that certainly structures the way I relate to things. So, there’s a personal side to why I’m interested in it.

But I first came up with the idea in a bar with my friend and colleague Erik Harms when we were in graduate school. We had just put everything we owned into storage in order to do our field research, and we were thinking about what it meant. The project might have been his idea. In any case I was immediately drawn to it as an alternative angle to thinking about consumption, the study of which has mostly focused on display and self-construction – the image of things. In contrast, my work is about the metonymic rather than metaphorical dimension of personal possessions – something our culture was much more explicit about in the 19th century but came to deny as part of the modernist project of positivism.

What research methodology do you use most?

If you mean in general, I primarily use immersive participant-observation in which I live in the midst of what I am studying. For this project things are different, since to do participant observation I would have to live in people’s homes and that is hard to achieve in our society! So I’ve had to try different things. So, I cannot claim to truly cross that divide in my fieldwork, but I try to minimize it by coming back more than one time. I try to keep the first interview about history and then come back later. What I really aim to do is help people deal with their stuff. And that approach only works for people who have a lot of it. For the minimalists, I can’t come up with as many excuses to come back. But people who want to organize their things or who want to clean out a space but feel overwhelmed by it often feel inspired by my presence. In some cases I visited people on a weekly basis to help them sort through their stuff because they have rooms of things that haven’t been sorted in over thirty years. So, they begin, partly through talking to me, to become concerned about the burden they are leaving the next generation.

I try to help people move, help people hold yard sales, or even just interview people while they have all their things in front of them. Some of those methods have a lot of potential, but it can be difficult to convince people such a close look a part of themselves they don’t show other people, or are even in denial about themselves. Lots of people are willing to talk to me but to actually let unpack their stored objects is harder. But I have many cases in which I have been able to sort through objects with people, unpack people that have moved, or clean out a storage unit. Those are really rich experiences because you see people have to face object after object and decide how to categorize it, where it goes, and face why they have it, why they packed it up in the first place when they moved. The decision process is typically rife with narrative remembrances and unexpected emotional reactions. It is not uncommon for people to break down in tears.

There’s a lot of personhood vested in those objects. But it also has a lot to do with memory. Sometimes it’s not other people who are embedded in the object but a former version of yourself or an event that you don’t want to lose or forget. People say that if they got rid of the object in question they don’t know if they’d remember it anymore, which means that things are not just extensions of how we display ourself but we believe that we remember things, we remember parts of ourselves and our pasts through the objects that we’re keeping, even if we’re not looking at them. Most of the objects I focus on are hidden away, but people believe that if they were to get rid of them, they would never be able to remember again. All those things become part of who you are and in a very fundamental way, because who are you if not your memories of who you were?

Let’s talk about your book, Modernity Bluff. Was that the outcome of your graduate dissertation at Cornell?

Let’s talk about your book, Modernity Bluff. Was that the outcome of your graduate dissertation at Cornell?

It is in many ways a child of my dissertation, which was not on the Congolese work I mentioned earlier but on Ivoirians (people from Côte d’Ivoire). Ivoirians also had an intense relationship to style and interest in “Western” culture and “becoming modern.” Many urban young Ivoirian men called themselves bluffeurs based on the word “to bluff.” This the idea of a bluff fascinates me. In poker, a bluff is meant to produce something out of nothing by making people think you already have the cards to make it happen, and that is precisely what the bluffeurs do. They produce an illusion of success that persuades people to treat them with respect, even though they have almost nothing to their name: no job, no money, not even necessarily a stable place to live. At the same time, most people know they are bluffing, that this is ultimately a performance, and that is a real puzzle, since in American culture we tend to scorn the poseur who pretends to be something they are not. But in Côte d’Ivoire the art of performing this mask of wealth is respected in its own right, in part because it indicates to their peers that they have the cultural capital to live like Americans or Europeans if only they had the money. And then there is a kind of fantasy involved, of living temporarily in another, magical kind of world. The friends of the bluffeur know that the bluffeur will be begging for money to get some food the next day. But a successful act of bluffing transcends all of that and reaches for a space of the imagination, of the possible. And it also produces doubt in the minds of those who don’t know you- maybe this is one of those people who has come back from Europe who really is rich now, a “parisien.”

Do men and women participate in bluffing?

It’s mostly men. Women participate in it but in a different way. They participate through men, for the most part. Their men fear them because women can easily call their bluff. You’re not allowed to refuse a woman anything in public if she asks for really extravagant stuff. You’re supposed to have enough money to fulfill any request. because you’re supposedly endlessly wealthy. So, they’re terrified of women who might take advantage of that situation and drain them. But in fact most women are interested in keeping up the illusion because they also benefit from it. They want to be with a successful guy. And dress is really important to them, too, but this whole conning aspect to it isn’t as much a part of it. They can’t really go out on their own to the same extent. In groups of women they can. But the place that they do the most showing off is at family functions, lifecycle rituals, things of that nature.

When did you gather the research that became the book?

I did my research in 2000-2001. It was right before the country (Côte d’Ivoire) fell apart. One of the things that kept me from doing as much follow-up research as I wanted to and made me keep having to transform the book I was writing is that the country was going through drastic political problems from 2002 to 2012. The government only controlled the southern half of the country. It didn’t extend all the way to the west either. You had all these different loosely coordinated rebel forces who were controlling different parts of the country. A lot of that had to do with identity and, I argue, it had a lot to do with modernity, too. The south thinks of itself as the seat of modernity, the source of “civilization” in West Africa and many people ended up wanting to exclude people that they didn’t consider to be true Ivoiriens by writing them off as foreigners. To them, it was the foreigners who didn’t know how to be modern, and as “savages,” they should not be allowed in the government.

How involved were you with those you observed in your research?

Close to full participation, though I was limited by the fact that I couldn’t be with them when they earned money through illegal means. At least, I didn’t consciously help anyone commit any crimes, although someone did borrow my backpack in order to steal some stuff and I only found out later. I was there when he got the keys that he used to do that robbery but I didn’t know he was going to use them to rob the person. I don’t only focus on image production but also on how they get any money at all. Not only were there few jobs but having a menial job was seen as shameful. They wanted to have what they called a real job or a desk job. That was where prestige was, and if they couldn’t get that it was too shameful to have a regular job, including as a taxi cab driver. I remember an Ivoirian who was a taxi cab driver said that he made great money, he did really well, but his neighbors wouldn’t talk to him. And the younger you are, the more this kind of honor system is important. So, they would do all kinds of petty crimes to survive and get money, mostly selling stolen goods to get extra cash. There were a lot of scams. Counterfeit money. Tapping into phone lines and selling minutes. Tapping into someone’s phone line in the middle of the night and let everyone make international calls all night and then put it back. Imitating policemen and collecting bribes. There was a connection between the conning of the results of their money, when they would pretend to have more money than they actually did, and the how they actually made any money in the first place.

I lived in the quartiers populaires, the popular or poor part of the city, and did as many things as I could that they were doing. Followed people around. We did a lot of “faire le show” (to make a show), when they were going out to celebrate and bluff. That was where this kind of illusion-making happened that was what all their work was for. They were happy to have me along for that. In fact, I added to it, to their showing off. But I spent long hours sitting around doing nothing with them, too, which they were doing since they didn’t have work, and talking about their dreams. I spent a lot of time trying to figure out what they thought the US and France – they lumped all of that together into the term “Beng,” which is the world of modernity. Everything was ultimately about getting there and being transformed by that place.

What did they imagine “Beng” was like?

Well, paradise on Earth, in short. A place where riches fall into one’s lap, where one cannot fail to become successful. This was such an article of faith that those who made it to Europe or America couldn’t come back until they had at least enough money to pretend to be vastly wealthy the entire time they were visiting home. And there was no way to go home permanently without truly making it big.

What do you hope the implications of this research will be for future researchers?

That book is really about globalization, about the way that the ideology of modernity travels. It’s a very hierarchical language in which the idea of social evolution is implicit, that some people are more advanced than others. I’m looking at the way that that gets incorporated into society on the ground and how people use it in their everyday lives in Abidjan, even in the micro-hierarchies between friends. The idea of modernity was there. Who was more advanced? Who was closer to civilization?

The ultimate conclusion of the book is that modernity itself is a kind of bluff. A lot of the success of so called modern societies has come from the projection of their own superiority as a justification for colonialism, through which Europe sucked the world dry. And the process is still ongoing, albeit in new economic and social forms. I would hope that my book would make people think more critically about hierarchy between societies in the world and the way that it’s produced, and think more sympathetically, as well, about the impoverished and their efforts to connect and be a part of the larger world.

Do you envision your book benefitting the general public?

I don’t think many in the general public will read it, as it does involve some advanced theoretical language, even as much of the ethnography is attractive to a lay reader. It’s largest potential effect will probably be through its use in the classroom, as students encounter this world I lived in and my interpretation of it and come to think in new ways about Africa and other places excluded from membership in the club of modernity. I’ve been happy to learn from people who have used it in the classroom that students respond quite well to it. One professor who had led a group of American students to Senegal after reading the book said that they were all pretending to be Ivoirians and making a “show!” Perhaps it will affect foreign policy in some kind of indirect way. I was called to DC to advise the new U.S. ambassador to Côte d’Ivoire, along with a bunch of other experts. And the book was a finalist this year (1 of 6) for the Melville J. Herskovits Award, which is given by the African Studies Association to the best nonfiction book in English about Africa each year, so I’m really thrilled and honored about the attention it has received.

Is there a subject in the field that you wish you knew more about?

Since I’m so interested in material culture, I wish I knew more about archaeology. There was no archaeology at my undergraduate institution and by the time I got to graduate school, I was very focused on sociocultural anthropology. Luckily I have some great colleagues here to teach me some about it!

Do you have any words of wisdom for young scholars trying to chart a career path for themselves?

Lévi-Strauss once said that cultural anthropology is not a job, it’s a vocation. It comes with an inner calling. I think you should be very sure that you hear that inner calling before you start down the path of cultural anthropology as a career. I think it’s a fantastic major because no matter what profession you go on to do, you will be interacting with humans and human culture, and anthropology gives you the tools to critically analyze and understand human behavior and patterns of thought. At the same time, it prepares you with critical reading skills and teaches you how to combine empirical description and narrative art in the service of a theoretical or interpretive argument. So an undergraduate anthropology major is well-trained for a wide range of jobs that require analytical thinking and the ability to successfully write or present a complex array of data in a compelling and persuasive way. Ethnography itself is also a skill that is increasingly sought after in the labor market. Cultural anthropology is also a wonderful career that combines a continual encounter with cultural difference, an opportunity to confront and perhaps even change the disparities and inequalities of human societies, and finally the chance to tackle some of the greatest theoretical challenges of human existence. On the intellectual side of it, it’s very rich. That said, on the professional side, it has become much more difficult to achieve a tenure-track academic position, in part because the proportion of tenure to non-tenure track professors has vastly decreased over the last 20 years. So, anthropology should be a passion that sustains you if you want to pursue a career in it.

What are your favorite things about your job?

I love that I get to think about and puzzle over the very things that have interested me since I was a child – why people act so strangely, why people think differently about the same things, how so much of everyday life is a performance, a performance that we convince ourselves is real. And even better, I have the privilege of telling captive audiences about these thoughts. I get to try to help people to step outside of their cultural lens and see the vast diversity of possibility, that things don’t have to be the way they are, that other people live in different ways that have their own positives and negatives, and together we can try to establish better ways of engaging with each other and with the world. In my more utopian moments, I get to try transform society for the better.

Do you have a favorite place? It can be anywhere in the world.

I did fieldwork with Congolese immigrants in Paris and got to live there for eight months, and I could have lived there forever. Not only because it is an inherently romantic city, but because it is a perfectly walkable city, a city on a humane scale, with many of the advantages of density and fewer of the disadvantages than most world cities. Although the Parisian winter is very grey and wet and the cold cuts right through your clothes. So, maybe summers in Paris and winters in Cadiz. That’s another of my favorite places. It’s an old city that reached its peak in the 16th century. It was the gateway to the Mediterranean, on an eight-kilometer long peninsula of sand. It was the only part of Spain that didn’t get conquered by Napoleon. They were the first Spanish democracy because the king had fled and they wrote a new constitution. There is magic in the light, and I immediately wanted to live there. I can think of a hundred other favorite places, so I’m just going to stop.

What are some of your guilty pleasure television shows?

I grew up without electricity so television has always been ridiculously appealing for me. I will watch anything, and then wake up from the trance wondering what happened. So the innovation of streaming things on the computer (which I project onto an old fold-up screen) has been very welcome. Instead of turning on a hypnosis device and ambivalently hoping to discover something of quality, my wife and I choose shows together – typically dramas like Boardwalk Empire or Breaking Bad and follow through an entire season, episode by episode. I think the narrative complexity and art production of these shows (the two I mention being great exemplars) really constitutes a new genre that goes beyond the television format, and has only become possible through digital media and the possibility of watching episodes back to back. But I don’t want to sound like I only watch things of artistic merit. I am also a fan of Project Runway – I find the combination of design competition with the humans under a microscope element of reality television and a hint of celebrity glamor to be endlessly compelling.

Do you have any free-time activities that you enjoy?

I have many activities I used to enjoy, like bicycling, board-games, music, and gardening – but since the birth of my son I no longer encounter that elusive creature called “free-time.” Now I only have “expensive time.” Luckily, he is a pretty wonderful activity all to himself. Now if I could only teach him to sleep through the night…

We’d like to thank Dr. Newell for his willingness and participation. If you’d like to contact him to discuss his research, you can find his information here: Faculty Listing – Dr. Sasha Newell.

Until next time,

- Categories: