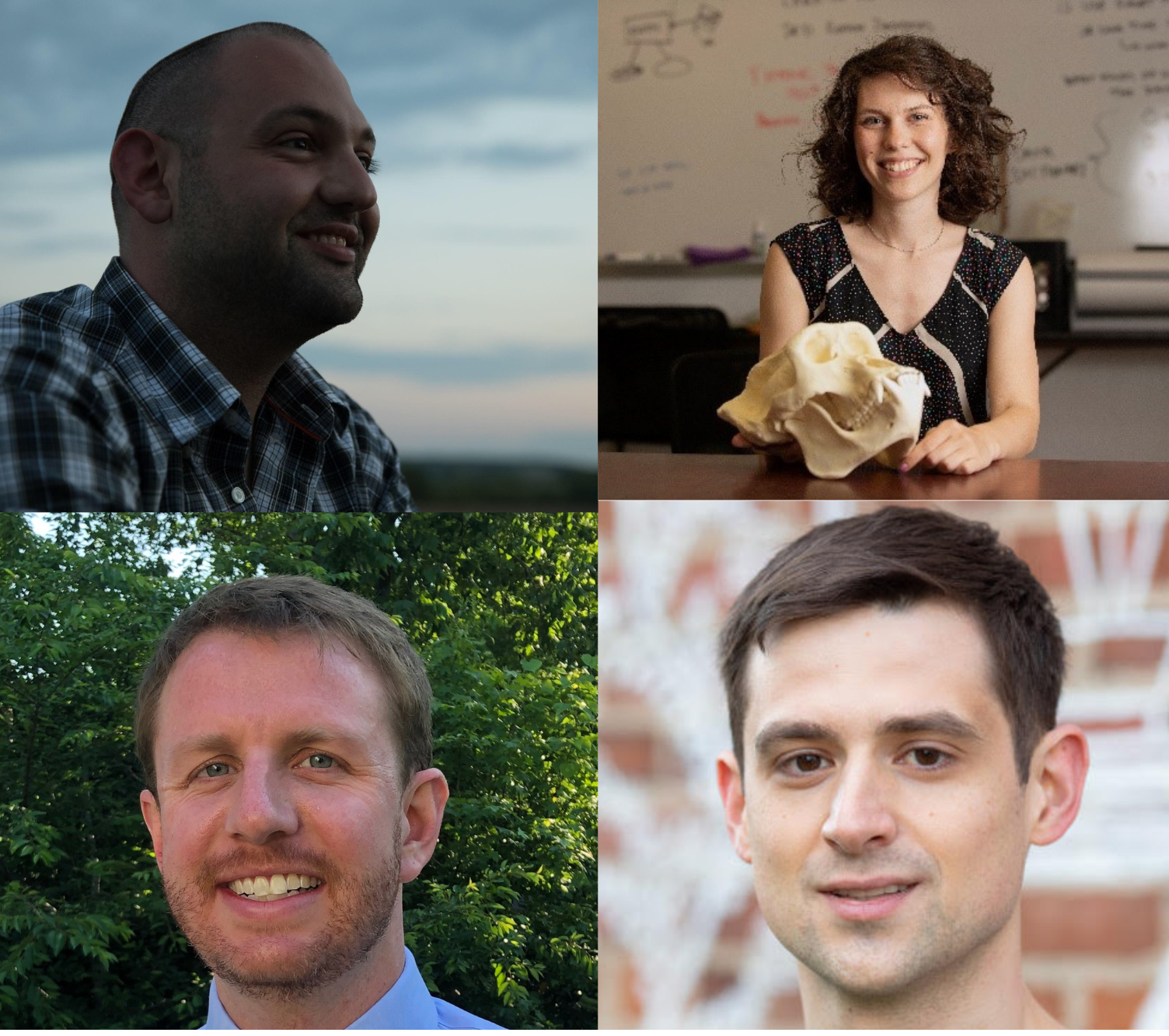

Meet the Faculty: Dr. John K. Millhauser

We pride ourselves on the research coming out of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology. Our faculty have contributed to the breadth and depth of the discourse in their research areas. Ranging from political economy to craniofacial growth, those research areas are as diverse as the complex human endeavor our faculty strive to analyze and understand. Ultimately, their fine research aids us in understanding human behavior and relationships, the foundations of human cultures and societies, which each of our faculty explores from a distinct perspective.

Today, we meet Dr. John K. Millhauser, who joined the Department of Sociology and Anthropology in the 2012-2013 academic year as an Assistant Professor specializing in Anthropological Archaeology.

Navigation

Personal History

Could you begin by giving us a little information on where you’re from?

I’m originally from Baltimore, but I’ve lived all over the country. Now that I live in North Carolina, I can say that I’ve resided in every region of the U.S. except the Pacific Northwest.

Where did you attend college and what did you study?

I went to Brown University where I got an undergraduate degree in anthropology focused on archaeology. I spent one semester on a study abroad program that was an archaeological field school in Belize offered through Boston University.

How did you discover archaeology and when did you know it was what you wanted to pursue?

Actually, I was pretty sure in high school, if not before that. As a child, I was interested in geology and paleontology and anything that involved looking for hidden things. As a teenager, I had the opportunity to travel to Israel and Egypt and was fascinated by the ruins that I saw. Between high school and college, I volunteered on an archaeological dig in Honduras and that’s what sold me.

When I got to college, there were many opportunities to study archaeology. To learn about the cultures of the Old World, like Greece, Rome, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, I could take classes in the Classics, Old World Art & Archaeology, and Egyptology departments—and I sampled a few of these. To learn about the New World, I took classes in the Art History and Anthropology departments. I majored in anthropology because I appreciated how it fostered a general interest in humanity and a specific interest in the people of a particular time and place, and because the department encouraged students to incorporate classes from other disciplines in their studies. During college and grad school, I worked on archaeological projects in Belize, Mexico, Portugal, Rhode Island, and West Virginia. So I have firsthand experience with a variety of cultures and time periods, from the Roman Empire to the Colonial U.S., but most of my experience is in Mexico.

Even with all of these experiences, it took me a long time to settle on archaeology as a career. Through college, my academic interest in archaeology paralleled an extra-curricular interest in the theater. I designed and built sets for plays and musicals. For a long time, I couldn’t see how to link the creative and collaborative work I did in the theater with my interest in archaeology. In fact, after I received an M.A. in Anthropology from Arizona State University, I took some time to throw myself fully into set design. But, I eventually found my way back to archaeology, in part because of my desire to keep learning about the past, and in part because I wanted to become a professor and share what I learned with others.

As I worked through the doctoral program at Northwestern University, I kept coming up against the question of why is it important for someone who lives in North America to study or to share about people who lived five hundred to two thousand years ago in Mexico. Why should anyone care? Over the years, I came to realize how even though the practice of archaeology – the excavations that we often do – is destructive, the work we do to interpret and present the past is incredibly creative and rewarding. I also came to realize just how important archaeology is to our understanding of the past, and why knowing about the past is important today.

So, why should we care?

Well, there are a bunch of reasons, but at the top of my list is that we should care about archaeology because it helps us to keep history fresh and relevant. I doubt that anyone would deny that learning about history is important. But the histories that we tell and retell can be limited. When we highlight certain people, places, or events in history, we hide or erase others. For me, archaeology is a way of stirring the pot. Archaeologists can study the major figures and events of the past, but the methods we use work just was well to study the cultures and social groups that are often left out of history texts, national narratives, or cultural celebrations. History may be written by the winners, but both the winners and the losers left behind trash, homes, burials, and all kinds of other stuff that we can use to learn about them. Looking holistically at the past might make us question the things we thought were most important. It could also reinforce those things that we already thought mattered. Archaeology also helps reinforce the idea that people all over the world are equally capable of developing advanced technologies and complex societies, unique religions, ethics and philosophies, and amazing artistic achievements.

Also, I can’t help but point out that people are curious. Archaeologists get to respond to that curiosity in ways that are tactile and material, finding artifacts that you can see and touch, excavating and sometimes reconstructing sites and landscapes that you can visit. We get to share what we find in ways that are tangible, and it is incredibly rewarding to share this with students and the public.

Teaching

What courses do you currently teach?

Currently, I teach Unearthing the Past: Introduction to Archaeology. This year, I’ve added Archaeological Method and Theory. Next year, I’ll add a course on the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica.

Could you describe your teaching style or philosophy?

My teaching philosophy revolves around two realities. First, students can get a lot of this information on their own, whether it’s through tv, the internet, or reading. So why should they take a class on any subject? One answer is that the professor is a guide, an expert who can lead you to the most important, relevant, or revealing cases. In this light, I see myself as a curator rather than a narrator. I am very open in my classes about my reasons for selecting each case we cover.

Second, and related, the past is not built from self-evident facts. What archaeologists know of the past is based on the kinds of questions that they ask and the ways in which they collect and interpret data. To the extent possible, I try to present data as distinct from interpretations and make the process of telling history apparent. I want to give students the tools to interpret the past rather than have them memorize a series of events. Doing so leaves open the possibility of alternate interpretations. Teaching this way puts a lot of responsibility on me to convince students why any particular view is valuable or legitimate rather than just tell them that it is.

I also like to use archaeology as a way to get students thinking critically about the past and how it’s relevant to the present. I try to have students work hands on and in ways that help them see how studying the material remains of any group of people, even contemporary college students, can be meaningful. They might study their own trash or draw a plan of their living space and compare it to the living space of people who lived seven thousand years ago. I also try to make it clear how the past is relevant politically and economically for people in the world today by using contemporary stories from the news about community archaeology, looting, and the like.

Current Research

Can you tell us about your current research interests?

I am continuing to work through the data from my dissertation research, which focused on small communities of saltmakers who lived and worked in the Basin of Mexico during the Aztec and Spanish empires. I’m using my findings to address a number of questions about economic and environmental inequality, the nature of life in small communities, sources of technological innovation, and the ways in which different kinds of work and labor produce social groups and shared identities.

I am also part of a team of researchers studying the society and culture of Tlaxcallan, a republic that developed in Central Mexico in tandem with the Aztec empire but in which power was distributed far more collectively than expected for the region or the time period. What’s been especially interesting is how the decentralized layout of the capital reflected its distinctive political organization. There were no enormous pyramids or central plazas. The city as a whole, rather than any particular district, reflected the power of the state. Now we’re trying to answer the question of whether life in this city was any different than life in other cities of the time. For example, did the more collective political structure reflect a more even distribution of wealth and well-being in general?

I’ve got some other potential projects cooking in Mexico, and possibly in North Carolina as well – but check back with me in a couple of years about those.

Can you tell me about the theoretical framework you’re developing?

For my study of saltmaking communities, I’ve been playing around with adapting the idea of “communities of practice” to archaeological research. This is a theory that developed from the ethnographic study of how people learn to work together without being directly taught, and how working groups create their own, unique social identities and practices. The challenge is to figure out how to show these processes of community building using nothing more than the material remains that people left behind.

What research methodology do you use most?

It depends. My work ranges from large scale surveys to the microscopic investigation of individual artifacts. Because I study a time period for which there are written records, I also use archival documents. I’ve become a pretty good hand at transcribing and translating the handwriting of sixteenth-century Spanish scribes, but I’m still a novice when it comes to Nahuatl, the main language of the Aztec empire. When I’m in the field, I am either outside collecting data from the surface of an archaeological site or excavating it, or I am inside studying the pottery, stone, and bones that people left behind. Here at State I’m working with some collections of obsidian, pottery, and plaster from Mexico, using techniques like X-ray fluorescence and thin-section petrography to learn about where the raw materials came from and how people produced and used tools and other materials. I also use GIS to understand spatial patterns in the data I collect. To conduct these studies, I’m building connections with scholars in colleges and departments across the university to help me do the best work possible.

What do you hope the implications of this research will be for future researchers?

Many archaeologists who study complex societies focus on the scale of the household, others are particularly interested in the state. Much of the middle ground is left out, and that’s where I see my contribution. That’s why I’m interested in the community scale of investigation. The communities where people live and the groups in which they practice their trade are, at particular times, the most important social connections that people have. I hope my work will help other archaeologists see the importance of investigating mid-level social groups and incorporating them in their models and interpretations.

Do you envision your research benefitting the general public?

I hope the way that I do my work creates ties of respect, interest, and equitability between the U.S. and Mexico. Latin Americans, if not Mexicans specifically, are one of the largest minorities in North Carolina and yet a voice that is largely absent in public discourse. Teaching classes, presenting public lectures, and creating exhibits are forms of outreach to Latino communities here in North Carolina. More generally, as I said before, my goal in practicing archaeology is to keep history fresh and relevant as well as to foster curiosity about the past, and I hope that my work fulfills that goal.

Further Questions

What do you feel are the biggest unanswered questions in your areas of interest?

The biggest unanswered question is: “Why?”

Students are often surprised to know that there are still so many unanswered questions about the past. The ones that tend to make the headlines are “When” and “Where” questions. When did people first use fire? Where did humans evolve? But behind these questions are the why questions. Why did people migrate around the world? Why did we settle down? Why did we start farming? Why did some people give up their autonomy to other people? Associated with these are questions about processes. How did we learn to domesticate plants and animals? How did we develop governments and religions? There aren’t singular answers to these questions – which is part of why it is important to study them at different times and in different places.

Is there a subject in the field that you wish you knew more about?

I wish I had more hands-on experience with the kinds of technological and ecological challenges that people faced in the past. The part of the field called “Experimental Archaeology” deals with recreating ancient technologies and I find it fascinating. Some of the people whom I respect the most in my field have the imagination, patience, or experience to work through all the steps.

What’s your favorite part of your job?

The best moments in the classroom have been when students ask questions that lead me to learn something new or think about the past in a new way. The best moments in the field are too numerous to list. Much of an archaeologist’s work is dirty, tiring, tedious, and mundane. If you didn’t enjoy it as an end in itself there’s no point in pursuing the career.

Do you have any free-time activities that you enjoy?

I like going to flea markets and yard sales. If you can imagine, I like the process of collecting and gathering and curating things. That’s as true to the archaeological side of me as to the set designer. There are certain things that I collect that are small and cheap and so I can go to the flea market and buy some dice or a deck of cards for a dollar and feel satisfied.

We’d like to thank Dr. Millhauser for sharing his work and his time. If you’d like to contact him to discuss his research, you can find his information here: Faculty Listing – Dr. John K. Millhauser.

Until next time,

The Department of Sociology and Anthropology

- Categories: